Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command Museum Chronicles

BCATP Chronicles

Last fall (2017), Clark Seaborn, aircraft restorer, offered me a flight in his vintage Fleet Canuck airplane. Flying south from Indus, we crossed the Bow River and then commenced a broad circuit over the coulees near the junction of the Sheep and Highwood Rivers. Clark wanted to show me a little bit of history, a building now more than 100 years old and something of a world traveller.

In the very early days of powered flight in France, an air race was held with aircraft flying between Angers and Saumur. To protect these delicate machines while they were on the ground, a lightweight and portable structure was designed by canvas and rope manufacturer Établissements Bessonneau. Using wooden stanchions supporting overhead trusses, this framework was then enclosed with custom-fitted tarpaulins and the whole structure was anchored to the ground with ropes and pickets. Thus was born the first Bessonneau hangar.

Finding itself in need of portable and easily built protection for its growing fleets of aircraft during World War I, the Royal Flying Corp, predecessor of the Royal Air Force (RAF), adopted the Bessonneau hangar for use in England and on the Western Front in France. Based on a standard size of 20 meters wide by 24 meters deep, hangars could be lengthened by adding additional stanchions and trusses. With a clear height of just over four meters, the Bessonneaus easily housed most types of military aircraft then in service.

At the conclusion of the war, the British hangars were disassembled and returned to England where they were put to use by the RAF, civilian flying clubs and private airplane owners. Some of the hangars, however, were given to Canada, along with a number of obsolete military aircraft. By 1920, two of these hangars had been transported to Morley, Alberta where they were reassembled, forming the nucleus of the Morley Air Station. Using Avro and de Havilland aircraft of the day, forestry patrols were carried out from this base along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

In 1921 the Air Station was moved to High River. Four years later, it was taken over by the Royal Canadian Air Force as No. 2 Operations Squadron but continued with forestry patrols, air photography and experiments with aerial spraying until 1931 when it was disbanded. During that decade, four Bessonneau hangars were erected along with a workshop building, garage and office building, storage buildings and a building for the radio transmitter and receiver. All four canvas-covered hangars were eventually enclosed with permanent siding, roofs and doors. When the province assumed responsibility for the protection of natural resources in 1930, fire towers were constructed across the eastern slopes and flying patrols by No. 2 Operations Squadron were discontinued. The station remained, however, and its Bessonneau hangars were used for aircraft storage.

With the declaration of war on Germany by Canada in September 1939, and the formation of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, activity at the dormant High River station accelerated. Number 5 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) was originally established at Lethbridge but as the demand for aircrew grew and the Plan expanded, the facilities there were needed for a new bombing and gunnery school. On June 21, 1941 Number 5 EFTS officially opened at High River with the first flying instruction occurring on June 29. Changes at the High River Station were considerable and included the erection of a new permanent hangar, barrack blocks, administration buildings, mess buildings, a station hospital and recreation facilities. The four Bessonneau hangars, now contributing to their second world conflict, remained in place and were used for the assembly and maintenance of Tiger Moth training aircraft shipped from Toronto.

On November 15, 1944, No. 5 EFTS was disbanded and all station personnel were transferred to other duties or returned to civilian life. In the ensuing years, parts of the station were torn down, sold and moved off or converted to other uses. The new hangar built in 1941 remains in place today and is used by a company constructing prefabricated homes. One of the Bessonneau hangars was purchased for use at the High River Fair Grounds and was moved to a site near what is now the High River Hospital. The Calgary Flying Club, following the fire that burned down its wartime hangar, moved one to the Calgary International Airport in the 1970's for temporary use. The fate of the remaining hangars is unknown.

On a blustery morning in November, I met up with three gentlemen in front of a large squat building in a farmyard southeast of Calgary, the very same building that Clark Seaborn had pointed out to me from the air some weeks earlier. Chuck, Ed and Jack Groeneveld had been born on this land in the original farmhouse built by their parents, John and Daisy. As a boy, John had come to Canada from Holland with his parents who settled in this part of the province. Daisy's parents had farmed nearby at the junction of the Highwood and Bow Rivers. As the eldest of the brothers, Chuck stepped to a door in the front of the building and invited us in. I watched as the three brothers gathered inside and began looking around the interior. And then, the stories began.

Chuck took us back to the reason the building is here on this farm. He recalled the intention of the High River Agricultural Society to move the fair grounds to a new site at the edge of the town. And so, in 1966, tenders were put out for the removal or demolition of buildings at the old location including the Bessonneau hangar that had been used as an exhibition hall. John Groeneveld heard about the tenders and submitted an offer of $1,200 for the building and that was enough to claim it. The only catch was that the structure had to be removed from town property within 30 days.

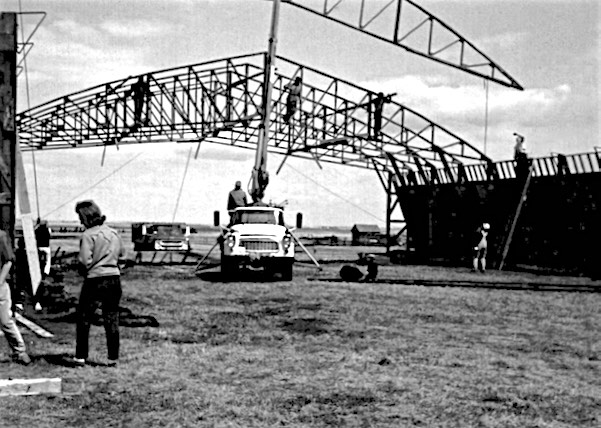

The brothers recalled their father rounding up relatives, friends and neighbors, and themselves, of course, to strip the old hangar of its shiplap roof and siding, remove the windows that had been installed under the eaves, and carefully take down the wooden trusses and stanchions. All the parts then had to be transported out to the farm for reassembly. Ed mentioned that the family was lucky to have made the acquaintance of John Hansen, a High River carpenter, who had actually helped move Bessonneau hangars from France to Canada after the war and who also supervised the movement of the hangar from the High River airfield to the original fairgrounds. Hansen once again supervised the takedown and the rebuilding at the farm. "Our Dad wasn't someone to take his time with a project," Ed commented. "He had John lay out and pour the concrete base for the stanchions and then make sure the building was put back up correctly." A truck-mounted crane helped with both the disassembly and the reassembly.

Jack spoke of the use of the building once it was on the farm. "I had taken my private pilot's license about that time and I yearned to have my own airplane and a place to keep it. Well, with the arrival of the Bessonneau hangar, I now had a place."" He spoke about his wife's mother who gifted the young couple $1,000 for a wedding present. "We bought an Aeronca Champ two-place airplane with that. So then we had a hangar and an airplane. What we didn't have was indoor plumbing in our old farm house," he added.

The building has served a number of purposes during its time on the farm. Equipment has been stored, it was occasionally filled with harvested grain and it has seen its share of airplanes. Along with extensive farming operations, the brothers Groeneveld operated a crop dusting operation out of the hangar as well.

After an hour or so of recounting some wonderful family stories, the brothers and I stepped outside for photographs. Jack gave me a collection of pictures, some of which appear with this story, and we said goodbye. It had been quite a remarkable occasion, the three brothers standing together and sharing memories of their lives and family, in an historic old building that keeps the memories of its life high up in the trusses overhead.

I discovered that Ed Groeneveld is a poet. He writes for his family and his poems are included in a family history book, the source of some of the material in this story.

I asked if he might like to write a poem to go along with my article. It is with great appreciation that I end this story of the Bessonneau hangar with Ed's poem.