Lancaster

Lancaster  |

Media

|

Media

Lancaster

Lancaster  |

Media

|

Media

[ photo: Graham Paine ] |

During the fall of 1987, four members of the newly formed Nanton Lancaster Society travelled to the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton, Ontario to find out just what was involved in restoring a Lancaster. Their aircraft, FM-213, was being restored to fly and would become the Mynarski Memorial Lancaster in memory of Andrew Mynarski, a Canadian Victoria Cross recipient who had been killed while flying in a Lancaster during World War II. Despite the fact that we were only planning to restore our aircraft to static display status, we were welcomed by the project's chief engineer, Norm Etheridge, and the others involved in the restoration including aircraft maintenance engineer, Tim Mols. Norm, Tim, and others at CWH patiently showed us all aspects of the restoration project and answered all the questions related to Lancasters and operating an aviation museum that we neophytes could come up with. Later, through trading some Lancaster parts with their museum, we were pleased to be able to play a very minor role in their wonderful restoration effort. |

As I sit back and think of my years at the Canadian Warplane Heritage museum working on the Lancaster, I wonder about how lucky I was then and how fortunate it was that the Lancaster was restored. There were many companies who seemed to become available to the project at just the right time. And, of course, key people as well such as Wes Raginski, Jim Gibson, Karl Coolen, myself, and Norm Etheridge. Wes and I had just graduated as aircraft maintenance engineers from Centennial College and were apprentices looking for a job in what was then a jobless market. Together, we travelled around Ontario looking for a chance to get a start in the aviation business. It was early in March 1983, and we were going to the Hamilton Airport to try our luck. After visiting (with no luck) every aviation company at the airport, we saw the Canadian Warplane Heritage hangar. We asked at the gift shop if we could look inside (without paying admission) and somehow we got to go into the museum. Wow! |

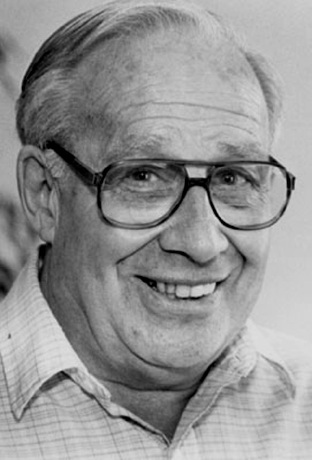

with renowned aviation artist Robert Taylor. [ courtesy Norm Etheridge ] |

We walked around and found the offices. We thought we might as well try our luck again. I walked in, hat in hand, and met the manager who said, "We just got a grant and the man heading up our project is here." Wow, more luck!"

I was introduced to the Englishman who politely said, "Hello. You two are the apprentices? Do you know anything about airplanes?"

"Yes," I replied, to which Norm said, "You're lying aren't you?"

In a rare moment of humility I said, "You're probably right, Sir." I remember him turning away from Wes and I and then turning back and saying, "Do you know anything about Lancasters?"

We both looked at each other and I said, "No. What's a Lancaster?" I don't know why but I suppose Norm saw something in us because Wes and I were hired.

At that time, Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum consisted of one old wooden hangar, a set of offices, and a gift shop. In the hangar was a collection of various World War II era aircraft -some flyable, some not, and a large collection of boxes.

The day we started Norm asked each of us to tell him what we were good at. Here we were, five apprentices, a very skilled leader, and an old airplane in a very cold, dark hangar with a skating rink for a floor. I asked Norm if this was a serious project and if he thought it would ever fly again. His answer was noncommittal but had a positive tone to it. That was good enough for Wes and I.

In the early days of the restoration we tried to organize the parts of the Lancaster in our area of the hangar. It became clear that Norm had an idea as to how to do this type of work. He led and we followed.

"Stormin Norman," as we used to call him, gave us directions as to what and how to do things. He used to say, "You can do things anyway you want, just as long as it is done my way." It turned out his way was always the best way. With Norm's growing confidence in us, came more confidence in ourselves. The crew of apprentices worked together and Norm led the way.

The money dried up in the summer of 1985. Norm accepted a full-time job as chief inspector for Field Aviation in Toronto and I followed him there. He had them hire me, I think, so that he could keep an eye on me.

In August 1985, more money was found for the Lancaster and Norm asked me if I would go back to the Lancaster project. My new job paid five times as much and I only lived a mile away from Toronto's Pearson Airport so my response was, "No way Norm. Good luck though, and call Wes!" But as quickly as my job with Field Aviation had come up, it disappeared. I told Norm I would go back to CWH as long as I could have a raise. It was a go and we reassembled under Norm's direction again.

The full-time crew was now Wes Raginski and myself. Norm would come in on Saturdays to discuss the progress that had been made and what we were to do during the following week. Norm always led the project. To the Lancaster crew, his word and his direction was it. I became his right (or left) hand man and Wes the other. This allowed us to progress in many different directions of restoration.

There were many times when Norm's aviation smarts came into play during the restoration. The wing spar bolts presented a real challenge. These bolts hold the outer wings. They were stuck in the holes in the spars on each wing and had to be removed. The forward bolts were especially difficult and many ideas had been exhausted including hydraulic rams, heating/cooling, big hammers, and group prayers -all with no results. We had worked for many days and not moved the bolts one millimetre. The bolts, I might add, were about one and one half inches in diameter and eight inches long. In aviation we call them "Jesus bolts" because when they fail that is who you see next. The final solution was to buy some very expensive diamond drill bits and start drilling from each end and meet in the middle. Then we would get the next size thicker and open the hole a little more. Eventually the entire bolt would be drilled out. We started and promptly began breaking the bits which cost about fifty dollars each. Norm taught us patience and persistence and never hinted that we might not be good enough to get those bolts out.

Well we did get them all out even though it took two months. One of those bolts took six weeks. Please understand that damage to any of the holes or the structure around the holes would have left FM-213 a permanent hangar queen, never to fly. It was crucial we did it right the first time. But it was that way on all of the projects that made up the restoration. Norm's motto was, "We have time to do it right but no time to re-do anything done wrong." As anyone knows in this type of work, it took years to get things done and each problem required a different approach and solution.

Norm, Wes, and I were paid to work on the Lancaster because it was necessary to have AME's continuously working on the airplane. The real heroes, other than Norm and Wes, were the volunteers. There was a core group who worked endless hours, doing grunt work. They deserve a lot of the credit for the restoration. Between 1983 and September 1988, many came and went but all made a difference to the project. Some of the special individuals were Jim Gibson, Karl Coolen, Fred Lowe, Greg Hannah, Gil Hunt, Chuck Sloat, and of course, Norm's wife Mary.

If you take any restoration or project, give it vision, proper management, dedicated people, and resources, it will succeed eventually. As with anything, sooner or later it will happen. FM-213 took the latter approach but it was destined to fly again.

During late 1987, the pressure was on to complete the Lancaster. Relationships between the full-timers and the volunteer crew reached overload and each time we felt at our wits' end, Norm pulled us back, helped us with our problems, and then sent us back to work again. Our differences were minor compared to the overall project -seeing the Lancaster fly again.

As a crew led by Norm, we started with piles of junk, restored, repaired, rewired, plumbed, and riveted. Our shared vision involved a diverse, broadly-based group of individuals and corporate supporters who came together, committed to seeing a Canadian Lancaster in the air.

During a high-speed taxi test on September 10, 1988, the Mynarski Memorial Lancaster left the runway for a few seconds. The pilots, Norm, and I held our breaths for those few seconds. The following day we went down the runway again and this time FM-213 took off and flew. Later that month the world was invited to watch as history was made with the official first flight. Canada had a flying Lancaster! I left Canadian Warplane Heritage after the inaugural flight to seek other employment. Norm stayed to oversee the flying of FM-213.

Norm Etheridge was, and still is, the only man I ever met who could solve problems without ever being defeated. My experience, problem-solving processes, and successes are a direct result of the knowledge and confidence Norm left me with. The Lancaster restoration could not have been successful without his guidance. Everyone else was important but he was the reason we succeeded. I personally spent about 14,000 hours on the project. Many people came and went but we all learned something about aircraft restoration and ourselves. Norm taught us all the skills required to fix old airplanes but more importantly the patience and self-confidence to know that, with the right attitude, any any problem can be conquered.

As our lives came together during the years we restored this magnificent aircraft, Norm always gave us respect and imparted his aviation knowledge to us without hesitation. Norm was voted the best Aircraft Maintenance Engineer in Canada and I was very lucky to work under his direction.

|

"Salute to the Lancaster" in 1997. |