Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command Museum Chronicles

My wife Madelyn and I were transferred to Senneterre, PQ in 1955, the year Janet, our first daughter entered our family. During my apprenticeship there as a Radar Technician, I was introduced to a Corporal by the name of Pat Brophy. I soon found out that Cpl. Brophy was an active Officer during World War II. His job was rear gunner on a Lancaster Bomber. Brophy and I worked shift work for four years giving us many hours to become more acquainted. I can recall asking him several times why he was so bald. He had no hair on his head, no eyebrows, no whiskers and he informed me also he had no body hair at all. When I would ask him why or what happened, he would shrug and not answer. I frequently asked him to tell me about his war experiences and his answer would be, "Not now Lloyd, I have to be in the mood." Many shifts went by and I sometimes wondered if the "mood" would ever strike and yes, it finally did. One night around 2 am, he asked me if my chores were complete and, naturally, I said they were. He said, "Make some tea and let's sit down." Some 50 years since, I will try to retell this story as best as I can recall: |

|

|

It was a soft June evening at an air base in southern England. A crew of seven men along with many others, sat in a group on the lawn waiting to be called to duty. "Maybe we won't go out tonight," they said to each other. It wasn't a long wait until over the PA system it was announced to the group to make ready and to stand-by your aircraft. In a short time, Brophy's crew was called and they headed for their aircraft. This was going to be their 13th operation. |

|

They took off and joined up with a large group of aircraft before heading for German occupied France. They crossed the English Channel loaded with bombs to be dropped at a predetermined target. However, this operation soon took a different turn from the previous twelve.

Soon the sky came alive with searchlights and anti-aircraft gunfire. Brophy, being the rear gunner, was busy trying to see if there were any enemy aircraft trying to attack them from behind. At the same time, Andy Mynarski was busy trying to defend the aircraft from the mid-upper gun turret. I might add the rear gunner's entry to the turret is a very small slit and when he moves left or right during firing, his exit to the fuselage is totally cut off. If the hydraulics fail, the only way to turn the turret is by a hand crank operated within the turret.

They hadn't gone far when they sustained a direct hit. The pilot told the crew to bail out because, "Our big girl has been hurt and she will not be taking us home."

Andrew Mynarski immediately knew Brophy was in trouble, with no hydraulic power. How could he help free Brophy from the tail turret? He went back to see if the crank would work the turret, but the turret was jammed tight. During the hit, the lines that carried brake fluid were ruptured and they were pouring fluid down the side of the aircraft which was now burning along with the engines. Mynarski had stayed too long trying to free Brophy and save his life. Mynarski's clothes were getting so hot that he had to leave. He saluted his buddy and mouthed, "Good night Broph" and proceeded to leave the aircraft. As soon as he hit the outside air, his clothes started to burn and in turn, started burning his parachute as he descended.

Brophy was now alone on a burning aircraft and steadily going down with the aircraft which was still loaded with bombs. He thought his time was near, so as a Catholic, he repeated, "Hail Mary, full of grace" over and over again as fast as he could. He could make out tall trees even although it was dark as the burning aircraft gave him enough light to see. Suddenly, he could feel the aircraft breaking up as the aircraft hit trees. He felt as if he was still in his turret but somehow he was flying in a different direction than the main part of the aircraft. All Brophy felt before he lost consciousness was the ground shaking twice probably from some of the bombs they had on board.

When Brophy regained consciousness, he took stock of his body and everything seemed to be okay. He was lying in a small ditch with no water. He then checked to see if he still had his revolver and his toothbrush, the only personal things he took with him when flying on an operation. No need for an overnight bag!! As he became more familiar with his situation, he removed his helmet and noticed all of his hair remained in it. At that moment, he thought nothing of it.

Off in the distance, he saw lights of a small village. He stumbled along, moving carefully as it was nearing daylight. When he arrived at the village, he found himself on a street with homes built close together. Each door was indented from the rest of the walls and in from the sidewalk. He guessed the time to be close to six a.m. From around the corner he heard approaching steps, much like marching soldiers. He stepped back into one of the doorways and drew his revolver. Suddenly, he felt a strong arm around his neck and another covering his mouth and he was yanked into the house. The man spoke English and told him to be quiet. He informed him that he was a member of the French Underground.

Days went by slowly as Brophy came to be more acquainted with the man who saved him and it also gave him time to mentally review all that had happened to him on the day of their mission that ended like a bad dream. He quickly found out just how the Underground worked when he was told that they were already working on getting him out of the area and back to England before the Germans found him and made him a prisoner of war. He knew now that three of his comrades were already being held as prisoners.

So the Underground put a plan into motion. The man that saved Brophy, took him the first leg of the journey, moving by darkness only and sleeping during the daylight hours. A second man took him on the longest journey yet, travelling by night and sleeping during daylight hours. A third man knew his way well so they covered their trip somewhat faster, again travelling by night and sleeping during daylight. Then the smell of salt water told Brophy that they were near the end of their trip. They stayed back from the water as daylight was approaching. They waited well into the next night before they left their hiding place, entering near waters-edge. It seemed forever until they could make out a boat. Soon, Brophy was leaving France behind. A second, much larger boat took Brophy to England.

He was guided back in daylight by an Englishman to a drop off point, close to Brophy's home base in England. (Broph had difficulty relating this part of the story to me. Mostly, Pat never let his emotions show. He liked to be more "happy go lucky" and "lucky" he surely was.)

Back at home base, there was a pub nearby and at this pub, one of the tables was considered by Pat and his buddies to be "theirs." He just had to go back and see if it was the same. As he approached the table, sitting alone was his pilot, sipping a beer. The pilot looked up and thought he saw a ghost and asked Brophy to, "Go away, don't bother me". After all, Brophy was still listed as missing. He knew that Mynarski had stayed to help Brophy but there Pat stood, bald, his black curly hair gone. In a short while Pat was able to settle the pilot down. He ordered a round, sat down and started telling him the story about how close he came to losing his life but had been lucky enough to return in one piece.

Brophy was sent to Scotland with the RCAF for nearly two months of Rest and Relaxation. Soon after he returned to duty. He was sent back to Canada, where he managed to get a leave to see his loved ones. Soon after, he was back flying and preparing to enter the Japanese theatre of war. However, luckily the war ended before he had to enter a war zone again.

|

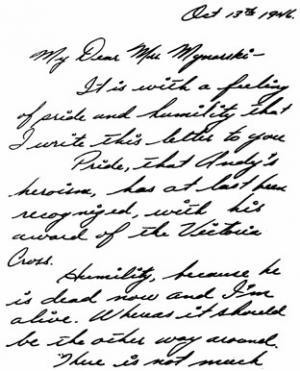

Pat re-enlisted in the RCAF during the Korean war. He took the same electronics course as I did in Clinton, Ont. He was posted to Senneterre, PQ. about six months before I was. Brophy and I worked shift work together for hours. One day Brophy said, "Guess what Foxy?" I"ve been asked to go to Winnipeg on Temporary Duty. I immediately asked, "What for?" "You remember me talking about Andy Mynarski? Well, after he lost his life trying to save mine, Ottawa awarded him the highest award to anyone in the Armed Forces. He was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously and his Mother accepted it for him. A school in Winnipeg was named in his honour, "The Andrew Mynarski School," and his Mother and the five of us survivors will be there at the dedication as guests of honor. I don't recall Brophy coming back to Senneterre because he was re-mustered into a different field of work. Pat was promoted to Flying Officer and was sent to St. Margaret's Air Station in New Brunswick. In 1959, my family and I left Senneterre in the summer to take up a new posting in Beaverbank N.S. (Halifax). On our way, we stopped at St. Margaret's Air Station to visit Brophy and his wife Sylvia. That was the last time I saw my buddy. . . During my retirement while living in Creston BC, I was watching a Remembrance Day program on TV and who should they be interviewing but Brophy. I don't remember what year it was but I was so pleased to see my buddy again even if was only on TV. He was a good friend. ,, |

|