Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

If an airman was to fly in bombers, he would be posted to a Bomber Command Operational Training Unit (OTU) for ten weeks. Here, the training was more serious and the flying much more dangerous than previously experienced, to some extent because of the dangerous mix of the novice crews and 'clapped out' aircraft that had previously flown operationally. He was now training as a member of a bomber crew and they would learn to fly operationally on an actual warplane. About 10% of Bomber Command's losses occurred while training.

"The instructors and admin officers, who wasted no time getting hold of us, organized the group into classes and laid out our syllabus. They dropped the word that within about ten days we would be teamed up in crews of five, each consisting of a pilot, bomb-aimer, navigator, wireless operator, and air gunner. Equal numbers of each of these trades had been brought together to form our course, and we were told that if any five could agree amongst themselves that they wanted to form a crew and fly together, the Air Force would oblige and crew them up officially. But at the end of the ten-day period, all those who had not made their own arrangements would be crewed up arbitrarily by the staff and probably, we guessed, by purely random selection."

Almost all the airmen were very young, even a man of twenty-five would likely be referred to as the 'Old Man' or 'Grandpa'. Within a crew, there were generally different ranks and nationalities, and they came from different walks of life. However, the men quickly bonded together to form a very special, tightly-knit crew. This bond was based on mutual trust, dependence, and shared experiences -both terrifying ones in the air and enjoyable ones while off duty.

This camaraderie was crucial to maintaining morale and efficiency in the air. Most felt that their crew was one of the best in Bomber Command. They generally spent many of their off-duty hours together as well as the first day or two of a leave.

"You were seven men brought together by conflict and you came to know each other's every mood and reaction, ability, humility, and likes and dislikes during your training and operational life together . . . Your crew were seven men who not only flew together but ate, drank, slept, and played together . . . You were 'one' and generally inseparable. Rank meant little between you, yet you knew the dividing lines between respect, authority, and familiarity."

Prior to the arrival of the four-engined bombers, the crews would be posted directly to an operational squadron, most likely to continue to fly the Wellington aircraft that they flew at the OTU. Beginning in 1943, the newly formed crews would proceed to a Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) where they would spend an additional five weeks becoming familiar with the Halifax or Lancaster bombers that they would be flying into combat.

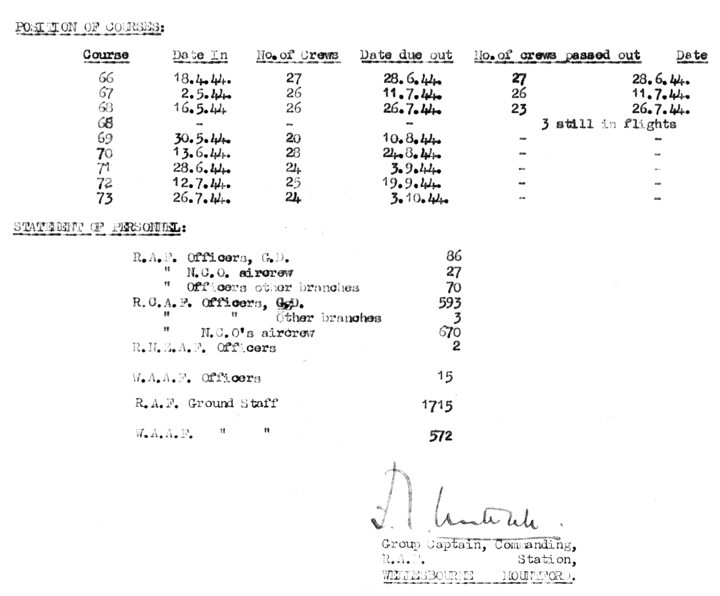

Bomber Command operated as many as twenty-two OTU's. Although none were directly administered by the RCAF, the majority of Canadian aircrew that would become part of the Canadian Squadrons were posted to 22 OTU at Wellesbourne. As the document below indicates, well over one hundred crews were in training at the OTU during mid-1944. As well, the unit itself was made up predominantly of Canadians, with over 1250 RCAF personnel on staff.

240 Canadians were killed while training at 22 OTU.