Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command

Day is beginning for the 2000 ground staff at a Bomber Command station on the bleak, windswept coast of eastern England. The target information for the next night has been received, in code of course.

At the far end of the airfield, armourers roll out the huge 4000 pound bombs and smaller 500 pounders and mount them on trolleys, ready to be towed out to the aircraft. Others pack the cases of incendiaries that will surround the high explosive bombs when they are winched into the bomb-bay. Other armament crews feed tens of thousands of cartridges into the ammunition boxes which will service the turrets. At the fuel dump, oil and petrol tankers or "bowsers" are filled. It will be mid-afternoon before the fueling of the Squadron's bombers is complete. In the dispersal areas, where the aircraft are lined up, mechanics rigorously check every part: engines, instruments, hydraulic systems. Test flights are completed and maintenance crews are often at work until minutes before takeoff.

At Station Headquarters the Commanding Officer and his staff check weather forecasts and plan the night's operation. Collecting and revising information, they work against time for the afternoon briefing.

In the locker rooms, members of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force pack parachutes and check the many items of equipment and clothing required by each of the 210 airmen. Other WAAF's are in the kitchens preparing rations and filling thermos flasks. Women at the station are also responsible for driving trucks and towing tractors and some are engaged in lighter maintenance work on the aircraft. The delivery of a bomber is often made by women of the ATA (Air Transport Auxiliary), who fly the aircraft in from the manufacturing plants.

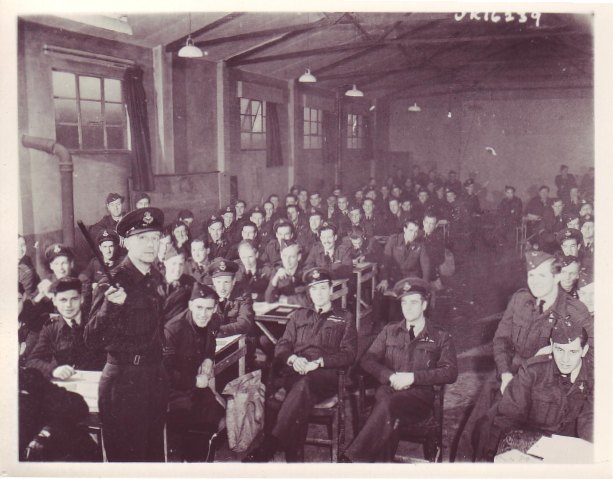

The aircrews gather in the briefing room, sitting together facing a stage, a map with the target hidden behind a curtain. The c/o begins by pulling back the curtain to reveal the target. The crews receive their information including precise courses, known defences, tactics to be employed, timing, operating altitudes, permissible radio frequencies, and weather forecasts. Maps are issued to navigators and bomb aimers.

The bomb loads are now in place. Armourers slot the Browning .303s through the doors of the turrets and feed in the ammunition belts. The last of the bombers is fuelled and the mechanics make their final checks. Following the traditional pre-operational meal of bacon and eggs, the crews are issued their flying gear, escape kits, and parachutes.

Smoking a last cigarette, crews are driven out to their aircraft. Once on board the men grope their way along a dark, narrow fuselage, stow their kit, and then settle down to the long pre-flight checklists. If all is well, the flight engineer gives the traditional thumbs up to the ground crew.

As daylight fades the four Merlin engines sputter to life one by one. The aircraft taxis to the end of the runway and the take-off run starts. It is a nerve-wracking affair for the crew as the aircraft strains to lift its tremendous bomb and fuel loads. Dusk is gathering as the bomber flies to a rendez-vous position where all aircraft on the operation from all squadrons will rendez-vous, and then continue to the target, climbing on track. In the hope of overwhelming the defences the bombers travel in a "stream" of numerous aircraft, very close together and travelling the same course, accepting the danger of mid-air collision. Although they rarely saw the other aircraft, their turbulance was often felt. |

|

Mid-air collisions occurred often during the many concentrated raids of the war's latter years. This Halifax had about nine feet of its nose section chopped away in an aerial collision over Saarbrucken on the night of January 13/14, 1945. Its skipper, F/O A.L. Wilson, lost his navigator and bomb aimer, both of whom were at their stations in the nose. With only three instruments on his panel working, Wilson brought the Halifax back and is seen here (centre) the next morning with the surviving crewmembers. |

|

The German defences are on alert, warned of the bombers' approach by their Freya early-warning radar. Awaiting the aircraft of Bomber Command are batteries of ground-based searchlights and radar-controlled anti-aircraft guns. Special units of "illuminators" (Junkers 88s) fly above the bomber stream dropping strings of parachute flares to assist those German fighters, not equipped with onboard radar. The aircraft may be attacked by enemy fighters on the way to the target and at any time during their return to base.

The bombers employ "Window," the name given to strips of aluminum foil released by the bombers to produce false echoes on enemy radar. Diversionary raids are staged, with the hope of drawing the Luftwaffe's attention away from the main target. The bombers' best defence, however, is cloud and darkness; their .303 calibre guns are no match for the 20mm cannon and specialized armaments of the Luftwaffe night fighters. The crew of a badly hit bomber had a one-in-five chance of escaping alive. The G-forces of a diving or spiralling aircraft were often overwhelming as the aircrew attempted to reach their stowed parachutes, clip them on, and make their way to an escape hatch.

The climax of every trip was the "run" over the target, often through searchlights and flak. The bomb aimers, spotting the red, green, or yellow target indicators dropped by the Pathfinder Force to mark their targets, give instructions for the bomb-bay doors to be opened and guides the pilot for the final few minutes of the bomb run. The aircraft lift 100 feet as their loads are released; then the doors are closed and, the weaving to avoid fighters begins again as the aircraft turn on to a westerly course for home. However, the crew must remain vigilant for the entire flight. Even in the landing circuit, bombers have fallen victim to enemy intruder aircraft and safety only really returns once the aircraft has returned to its dispersal.

The English coast, often treacherous to airmen with its low-lying fog, is sighted. Ground staff cheer as their "own" aircraft approaches; others anxiously await crews who will be lucky to complete ten trips in these grim days. Longer routes, adverse weather, and the success of the Luftwaffe defences have all contributed to increased casualties.

Stiff and weary, the airmen climb into the waiting truck and head for the debriefing hut. There, fortified with coffee and rum, they go through the necessary questioning about the night's events. Another operation has been successfully completed; one more day of war is over.