Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command

Bomber Command  |

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

|

|

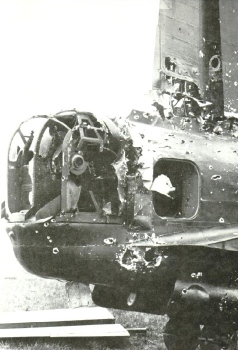

The gun turret of a Bomber Command aircraft during a night operation was the coldest, loneliest, place in the sky. Whereas other crew-members enjoyed some comfort from the proximity of others in the forward section of the aircraft, the mid-upper gunner spent the trip suspended on a canvas sling seat, his lower body in the draughty fuselage and his head and shoulders in the plexiglass dome. The rear gunner was even more removed from his fellow crewmembers and any heating system. Suspended in space at the extreme end of the fuselage, "Arse-end Charlie" was subject to the most violent movements of the aircraft. Squeezed into the cramped metal and perspex cupola, the rear gunner had so little leg space that some had to place their flying boots into the turret before climbing in themselves. Many rear gunners removed a section of the plexiglass to improve their view, so with temperatures at 20,000' reaching -40 degrees, frostbite was a regular occurrence. And through the entire operation, the rear gunner knew that the Luftwaffe fighter pilots preferred to attack from the rear and under the belly of the bomber, so he was often first in line for elimination. During World War II 20,000 air gunners were killed while serving with Bomber Command. |

|

|

During a Bomber Command operation, the only sounds the gunner would hear, aside from the constant deafening roar of the engines, would be the hiss of the oxygen and the occasional crackling, distorted voices of other crewmembers in his earphones. From take off to landing, at times for as long as ten hours, the air gunner was constantly rotating the turret, scanning the surrounding blackness, quarter by quarter, for the gray shadow that could instantly become an attacking enemy night fighter. The air gunner's closest friends were likely his crewmembers in the forward section of the bomber and the relaxation of his vigilance for even a moment could mean death for them all.

|

|

The primary role of the air gunner was not to shoot down enemy aircraft. Rather it was to perform the role of a lookout. After hours of staring into the blackness, his shouting into the intercom of, "Corkscrew port now!" would have the pilot instantly begin a series of violent evasive manoeuvres, throwing the heavy bomber around the sky. Generally if an enemy fighter pilot knew he had been seen, no attempt would be made to follow the bomber through its gyrations. Rather he would seek out another aircraft, hopeful that it might have a less alert air gunner. Many air gunners completed their tour of operations without firing a single shot "in anger," but the stress they were constantly under was equal to those who, with guns ablaze in the night, became part of brief, terrifying, life and death battles in the night with enemy aircraft. At the beginning of the war "Wireless-Airgunners" played a dual role, being responsible for radio operations as well as the operation of the gun turret. Later, with the advent of the four-engined bombers with seven crewmembers, this combined role was no longer necessary. |

|